In this blog post, REFUNITE’s Middle East Project Manager, Sacha Robehmed, reflects on her recent trip to Erbil, Kurdistan region of Iraq, with Product Manager, Vytas Bradunas, to test the new REFUNITE web platform.

What’s in a Name – or Four Names?

Testing and Localizing m.refunite.org with our Iraqi Users

*For all photos where faces are clearly shown, formal consent was given. Names have been changed to protect anonymity.

Back in November 2016, we celebrated the launch of our new web family tracing tool after a complete rebuild and redesign. With people increasingly owning smartphones, and growing numbers of users finding REFUNITE through Facebook’s Free Basics, web is key to REFUNITE’s growth – and ultimately, to people finding each other.

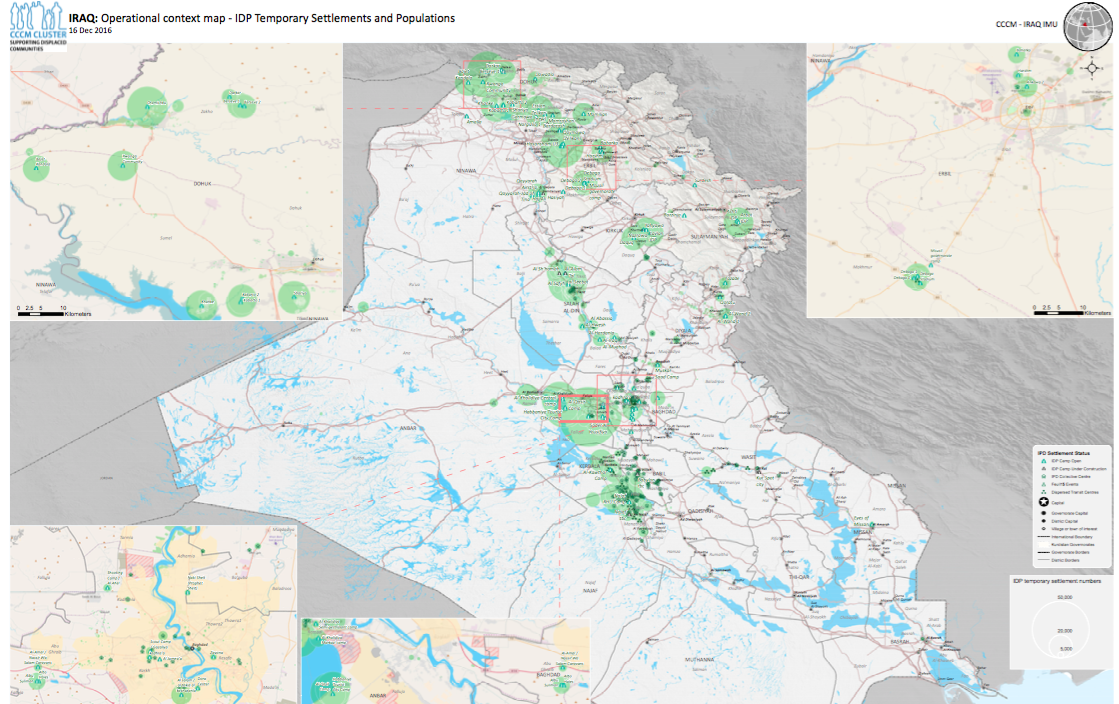

In 2016, we saw the largest number of REFUNITE’s new registrations via web come from Iraq – 40%. Iraq has a high smartphone penetration rate, and approximately 10% of its population – 3.5 million people – are internally displaced. Localizing (tailoring REFUNITE’s new web platform to the specific contextual and linguistic needs of Iraqi users) to give them the best possible user experience was our top priority. In preparation for the release, we had been working on Arabic translations remotely for months, with the help of a coding bootcamp in Erbil for refugees and IDPs, Re:coded and network of translators Global Voices.

The REFUNITE platform is about enabling people to find their missing loved ones, but we’ve found that the information people need in order to do that varies from place to place. Among Somalis, for instance, a population where thousands of people can have the same name, we learned through field research that gathering information about “clan” was significant in helping people distinguish each other. Collecting this information when a new user registers can be a vital step in helping their loved one recognise them.

What would the key information field be for Iraqis? We went to find out! In the last week of November 2016, web team lead Vytas Bradunas and I travelled to Erbil, in the Kurdistan region of Iraq, for focus group discussions and usability testing. It was time to hone in on the key information people use to identify each other in Iraq, and to ensure the new website was intuitive to Iraqi users (what’s know as “usability testing”), giving them tasks so we could observe how they navigated the registration, search, and messaging processes. We ran seven focus group discussions and six one-on-one usability tests, with a total of 52 IDPs – men and women of different ages, from different parts of Iraq, living both in camps and in non-camp settings in Erbil.

On our first day, we spoke with 2 groups of fellows from Iraq Re:coded, as well as conducting one-on-one interviews for the usability tests. A diverse group, all the Iraq Re:coded fellows are learning how to code. We met them at their training center on the outskirts of Erbil.

The first day was particularly insightful in terms of of some positive observations about technology use. All the participants had Facebook, with almost everyone using their phone number not an email address to login. This is helpful for us to know, as we also ask users to sign up with their phone number, so if Iraqis are used to doing this for Facebook it’s likely that this will be straightforward for them when registering with REFUNITE.

Another key finding on our first day was that people were comfortable switching between numeral systems. Even when the phone language was switched to Arabic, all contact numbers are saved in the numbers 0-9, rather than those used by Arabic speakers (٠ – ١ – ٢ – ٣ -٤ – ٥ – ٦ – ٧ – ٨ – ٩). Designing for right-to-left languages like Arabic can be challenging, but this insight meant that numbers on the English language platform could also be used for the Arabic version.

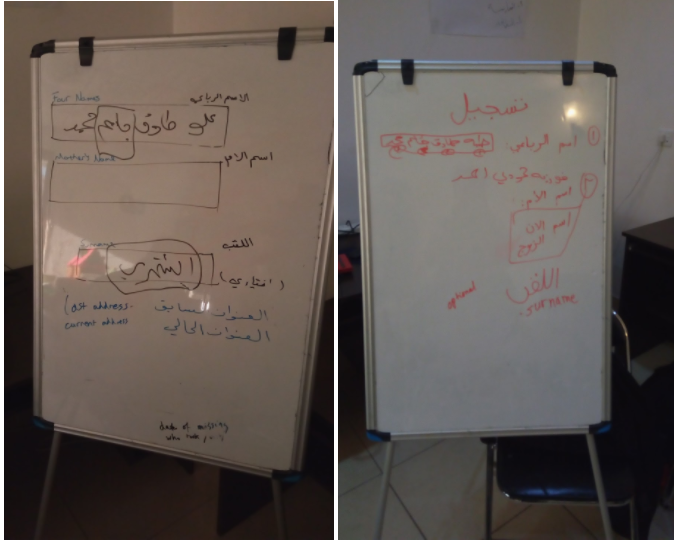

We also began to uncover insights around naming conventions – Iraqis take their father’s, grandfather’s, and great-grandfather’s names as second, third, and fourth names respectively – and important information fields, namely “mother’s name.” These initial insights allowed us to dive deeper on the second day.

Vytas and I headed to the touristic town of Shaklawa, 50km north of Erbil city. There, supported by Un Ponte Per, we ran focus groups, and began to dig into the information fields by sketching out possible registration pages, looking particularly at location information and naming conventions.

Our first focus group was a group of women from Anbar and Mosul, most university graduates. After similar responses on technology use to the previous groups, we tried something new. We worked together to co-create a registration form, including new, key fields. Initially a quiet group, the conversation evolved to an intense debate as to whether or not a “mother’s name” field should be included. One woman said she would not want others to know her mother’s name, and would not even want to sign up to a service like REFUNITE in her own name, instead preferring to use the name of her husband or son. The other women in the group though were keen to emphasise that this was an exceptional, more traditional and conservative, attitude. Weighing up the need to ask for certain identifying information, the value of that information to identify others, and the risk doing so discourages users from registering, our focus group discussions helped us decide to include “mother’s name.” (Incidentally, “mother’s name” is on Iraqi ID cards.) However, we did hear from women in other focus groups that they might register on Facebook as their brother or their son to avoid unwanted male attention. A platform like REFUNITE, separate from Facebook and with the specific purpose of family tracing, is less open to ambiguity in a way that we hope female users might be more encouraged to sign up as themselves.

With a better idea of what our new registration page should look like, we then ran focus groups and usability tests in Baharka camp north of Erbil city, again kindly supported by Un Ponte Per. Here, our focus groups progressed to basic prototyping – we handed out paper versions of the likely registration form, and asked our focus group participants to fill them in. These forms included “الاسم الرباعي” or “four names”, “اللقب” or “surname”, and “اسم الأم” “mother’s name.”

While those displaced from urban locations like Mosul could complete the paper prototype registration forms fully, some of the IDPs in the focus groups from more rural locations could not read or write. With limited literacy skills, they still used Facebook and had smartphones, but they were unable to complete the registration forms – both the paper prototypes and online – without assistance. We aim to make REFUNITE available to all, so the focus group discussions in Baharka camp were a much-needed reminder to Vytas and myself about the limitations of web when it comes to accessibility and literacy.

While we were confident that we had the makings of a web product that would help people find their missing loved ones easier, the high levels of illiteracy amongst rural populations in the camp reinforced the need to consider other types of access to REFUNITE, such as a call center, in 2017.

The insights gathered in Erbil have led to significant changes on the website. The first week of January, REFUNITE’s web team deployed changes to the information fields and more nuanced translations. This improved user experience will ultimately help more people to register themselves search for and hopefully find their missing loved one. We’ve been encouraged to see registrations in Iraq increase from around 50 per day in November, to more than 200 per day in January.

The research in Erbil in November also helped give us a more nuanced understanding of our users – such as the more conservative attitudes around online behavior among some women, and broad trends of displaced people from urban areas tending to be more literate than those from rural areas. After meeting our potential users, we go forward designing with them in mind. We will also continue to test new iterations with users in Iraq, making sure REFUNITE is serving their family tracing needs.

27 January, 2017.