Music is therapy for the Refugee All-Stars, who met each other after a war in their W. African homeland.

For the members of Sierra Leone’s Refugee All Stars, “African music” isn’t just a phrase; it’s a sentence. Or at least that’s how they used it at World Cafe Live Monday night, as if the music needed no subject or object to be complete.

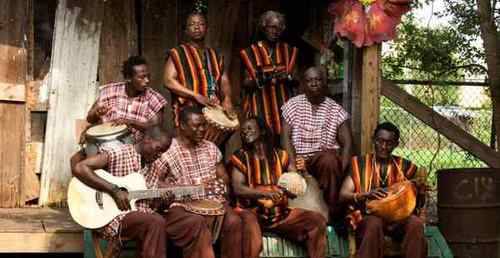

For a time, music was the closest to a home the group’s eight members had. As chronicled in the 2005 documentary named for the band, they came together in refugee camps after being displaced by the civil war in Sierra Leone, a grisly affair in which tens of thousands died and many more suffered amputations at the rebels’ hands.

Though they have since returned to the country’s capital, Freetown, the All Stars’ songs remain attuned to the fragility of peace and the healing power of community. “I believe dancing is therapy,” said the group’s leader, Reuben Koroma, urging the seated audience to join each other on the floor. They didn’t need to be asked twice.

The twin wellsprings of the group’s sound are Jamaican reggae and South African mbaqanga, the sound familiar from Paul Simon’s Graceland. The song “Muloma,” meaning “let us be united” in the Mende language, worked with a skittering guitar figure and the enticing vocals of Mohamed Kamara, whose limbs swiveled as he sang. “Living Stone,” another of his songs, was built on the familiar offbeat chink of reggae rhythms, the chop and sway of staccato chords, and slide trombone mingling irresistibly.

Most of the group’s members took a turn in the lead vocal spot; Alhaji Jeffrey Kamara, also known as Black Nature, added a throaty, high-speed rap to “Gbrr Mani (Trouble),” which laments the social breakdown caused by dissolving marriages.

In “Jah Mercy,” the evening’s most plaintive song, the bass was heavy and the guitars seemed to lag almost imperceptibly behind the beat, as if the social ills the song lamented were making the world grind to a halt.

For the most part, the songs surged forward, goaded by the unpredictable accents of Christopher Davies’ drums. The grooves stretched out until time dissolved, as if they could have gone around in circles forever. They made their own world, and invited the audience to live there for a while.

Source: The Philidelphia Inquirer

By Sam Adams